A brief history of the Efus Safety Audit

Drawing a clear picture of the security situation in a city and taking into account different perceptions of security held by different groups within that city is a crucial prerequisite for implementing effective security policies. The European Forum for Urban Security (Efus) has long promoted the centrality of this approach. The 2008 Guidance on Local Safety Audits: A compendium of International Practice first outlined the Forum’s ambition to systematise evidence-based information collection in its projects and in the support it offers to its members. A follow-up to the 2008 Compendium, the 2016 publication of Methods and Tools for a Strategic Approach to Urban Security embeds the Safety Audit in a larger framework: The Strategic Approach to Urban Security.

The Efus strategic approach to urban security

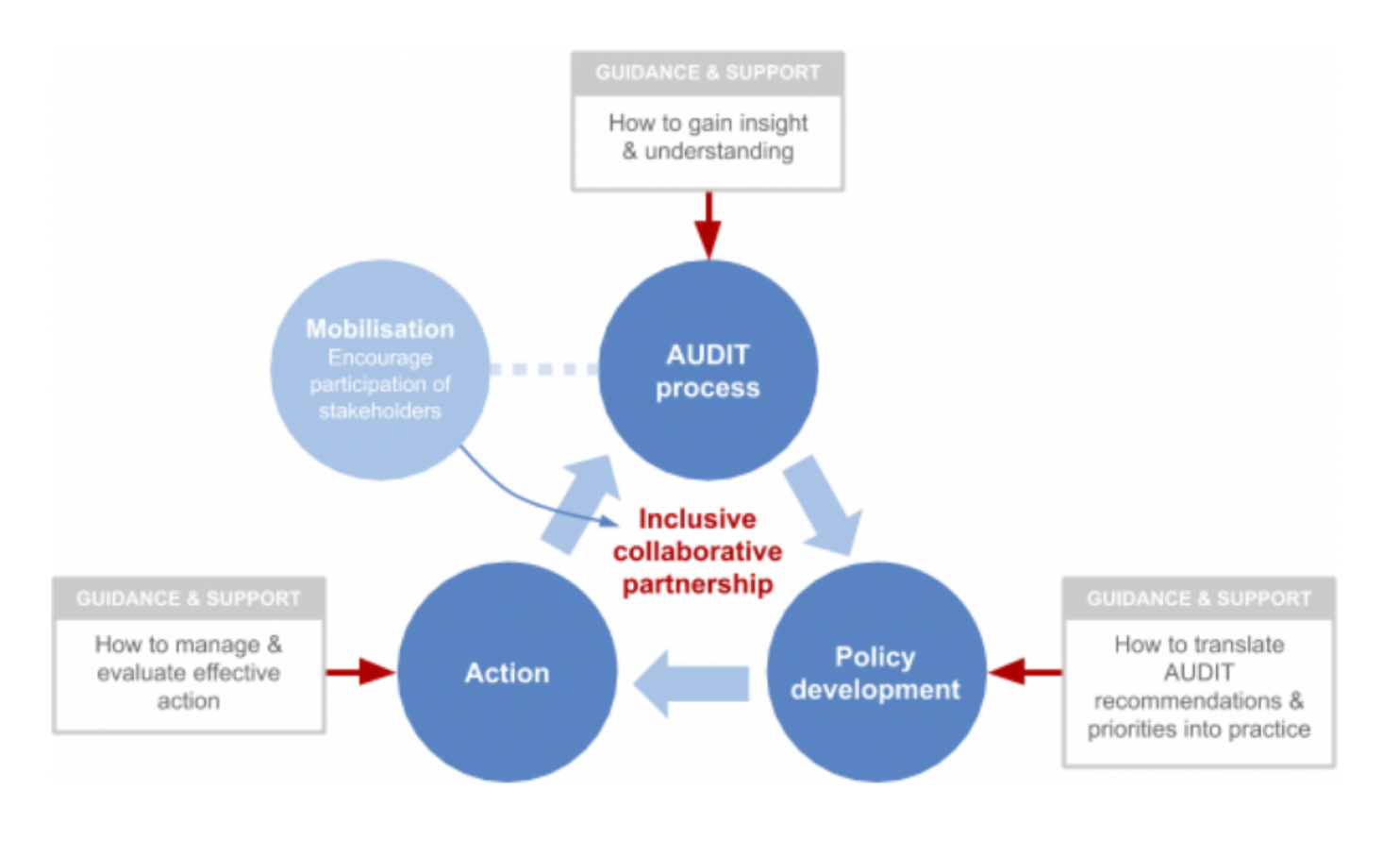

The approach consists of five elements (Efus, 2016):

- The safety audit: learning about, understanding and analysing elements of the local security situation

- The strategy: translating the findings of the audit into goals and objectives

- The action: fleshing out an action plan and guaranteeing its efficient implementation

- The evaluation: assessing the implementation and the impact of the action

- The mobilisation and participation: engaging in a continuous effort to include all stakeholders and foster participative processes

Not a linear process but rather a circular one, the approach highlights the principles of inclusion, participation and evaluation. The tenet of the safety audit is to gather comprehensive knowledge on the security problems of a territory so that the strategies to be developed subsequently respond to real needs.

New tools, new methods and a (re)newed focus on participative processes.

Since the publication of Methods and Tools for a Strategic Approach to Urban Security in 2016, Efus has continued to work on projects and partnerships that nourish its repertoire of tools and methods to support security actors on the local and regional level. The design approach and human-centred methodology employed by the Cutting Crime Impact (CCI) project inspired Efus to mobilise this knowledge and advance its strategic approach to urban security. One of the key tenets of the CCI methodology is to learn about the needs and requirements directly from the end-users – in this case law enforcement agencies and security policy makers. This approach brings along a set of tools and methods that are tailored to gather information from the source: focus groups, immersion, journaling and insta-ethnography, to name only a few.

In a world where the security challenges that local and regional authorities face are ever evolving, it is becoming increasingly important to have the right tools to learn about these challenges. Citizen initiatives are multiplied and public participation is becoming more common, both in the conception and in the implementation of urban security policies. Too often, this participatory effort is reduced to consultative participation. The co-production of urban security policies is often considered too difficult to implement and the fear of unforeseen consequences might further demotivate municipalities to foster public participation (Efus, 2016).

Through multiplying sources of information and fostering an environment in which every group’s realities and perceptions of urban security are taken into account, the safety audit prepares the stage for the co-production of urban security policies that reflect the needs of inhabitants. The inclusion of a diverse and representative range of stakeholders in this work is a first step towards co-production. The involvement of existing civil society organisations – local security councils, youth clubs, minority or parent-teacher associations to name only a few – can facilitate this.

Feelings of insecurity as an additional indicator of the urban security situation

In its 2017 Manifesto, Efus committed to continue “targeting underrepresented and marginalised types of victimisation (…) to ensure that our knowledge of such phenomena and the effective means of fighting these are improving” (Efus, 2017, p.37). Some forms of crime and delinquency instill a stronger sense of emergency than others, yet it is important to keep in mind that inhabitants are often mostly concerned with daily security and the feeling of safety. The fact that it is often the least victimised public that is the most fearful is called “the fear of crime paradox” in criminal literature. Feelings of insecurity don’t only have an impact on the individual but also on collective well-being and can inform the population’s political and economic behaviour, as well as their behaviour in and use of urban public spaces. This is why the updated guide on Safety Audits puts additional emphasis on ways to identify feelings of insecurity.

The CCI project focuses part of its work on measuring and mitigating feelings on insecurity. Generally, victimisation surveys tend to ask respondents how worried they are about crime in a bid to measure the level of fear of crime. CCI research argues that the conceptual formulation of “fear of crime” is an umbrella term that includes a range of emotional reactions and cognitive processes. Focusing solely on the “fear of crime” can omit the nuances of people’s feelings of insecurity. The Design Against Crime Solution Centre at the University of Salford developed a conceptual framework that aims to operationalise the different facets of feelings of unsafety impacting the lived experience. The ‘Feelings of Unsafety’ model includes individual perspectives on unsafety – from ‘assumed situational vulnerability’, ‘situational anxiety’, and ‘fear’ in the face of immediate threat. It includes two facets arising after crime victimisation – immediate ‘shock, anger and distress’ and the medium to longer-term processes of dealing with victimisation. Finally, completing the cycle is the rationalisation of the experience. This process feeds into the ‘background context’ as individual experiences are shared with family members, friends and neighbours and this in turn informs wider societal concerns, anxieties and political priorities.

In this way, the model seeks to illustrate how the ‘background context’ for feelings of insecurity both nourishes and is nourished by individual experience. Identifying this conceptual structure is important for measuring feelings of insecurity in a way that can provide actionable understanding — particularly in relation to specific demographic groups and situations. Understanding the different factors that shape ‘insecurity’ is fundamental to the generation of effective strategies for mitigating their impact (Davey and Wootton, 2019).

Avoidance mapping as a way to give disadvantaged youth the opportunity to speak up

One example of a participative tool that can facilitate learning about residents’ feelings of unsafety is Avoidance Mapping. Perfect City is a New York-based working group that promotes civic engagement for the most marginalised and encourages the reinvention of public spaces in collaboration with locals. They engage with young people from the city’s Lower East Side neighbourhood to learn about their experiences with gentrification, displacement and safety. Perfect City developed a mapping tool that encourages participants to reflect on how they navigate space by asking them what areas they avoid on a daily basis. The reflection on young people’s experiences bring about new understandings of how they perceive their city, including safety issues.

Through the Avoidance Mapping exercise different points of view can be collected and help construct conversations about bias, exclusion and displacement – and how they impact young people’s perception of safety in their own communities. Perfect City has developed versions of this exercise to work with domestic violence shelter residents in New York City and began planning work with youth in Cleveland, Ohio.

A new space on Efus Network to facilitate the exchange of practices and experiences

A dedicated space on our online platform, Efus Network, will include the methods and tools employed by the CCI project’s partners – as well as by partners of other Efus projects – to understand, measure and mitigate feelings of insecurity. Their experiences give shape to the conceptual framework developed by the CCI researchers and highlight the relevance of taking feelings of insecurity into account when drawing up a prevention and security strategy. The tools used by the State of Lower Saxony (Germany) and the department of the Interior of the regional government of Catalonia (Spain) include surveys specifically conceived to measure different aspects of insecurity and exploratory walks to foster the active participation of inhabitants.

Inspired by the lessons learned during the CCI project and Efus’ continuous exchange with cities and regions in Europe and all over the world, the Safety Audit guide will support local and regional authorities in their efforts to better understand the security situation in their cities and make the process of information collection as inclusive and representative as possible.

Efus members are now able to find additional information on the strategic approach and safety audits on Efus Network, via this link. You can already find a number of tool practice sheets and examples of how they were used.

A version of this article was published in the CCI Newsletter of October 2020

References

Efus (2016) Methods and Tools for a Strategic Approach to Urban Security, available from: https://efus.eu/en/resources/publications/efus/11191/

Efus (2018) Manifesto: Security, Democracy and Cities – Co-producing Urban Security Policies. The Manifesto was published in the wake of the Security, Democracy and Cities international conference organised by Efus, the City of Barcelona and the Government of Catalonia on 15–17 November 2017, in Barcelona. Available from: https://efus.eu/en/resources/publications/efus/3779/

Efus (2007) Local Safety Audits: A Compendium of International Practice, available from: https://issuu.com/efus/docs/efus_safety_audit_e_web_e504a3fc4d052a

Davey and Wootton (2019), PIM Toolkit 4: Report on feelings of insecurity – Concepts and models adapted from Davey, C.L., & Wootton, A.B. (2014) “Crime and the Urban Environment: The Implications for Wellbeing”, in Wellbeing. A Complete Reference Guide (Eds) Burton, R., Davies-Cooper,R. and Cooper, C. Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester (UK)

CCI October 2020 Newsletter